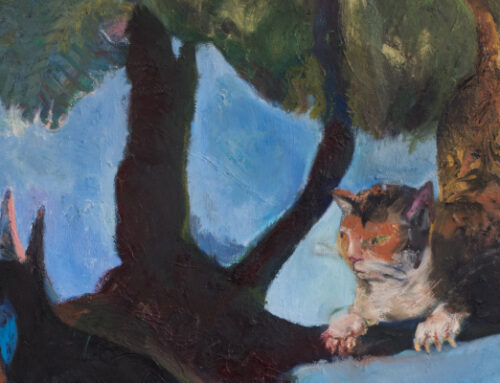

Impossible Shrines, Terra cotta clay, Thai kozo paper, sugar, wire Remington Quiet-Riter type, 5.5’x5’x5.5’

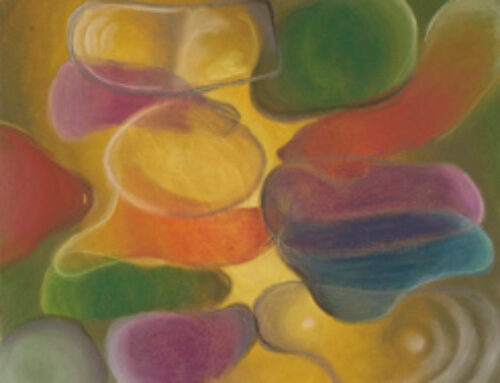

Float/Porena, Glaze, collagraph prints on thai kozo, fibre glass, 1’x5.5’x3’

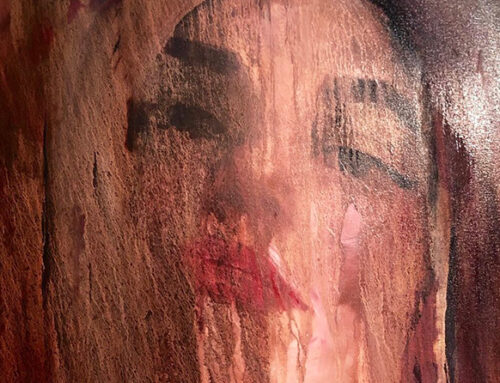

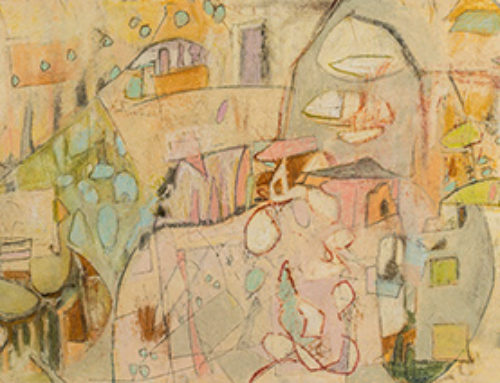

Measuring to a Saint,

Collage printed with terra cotta, porcelian, waxed linen thread, 5.5’ x 3’ x 10’

JENNIFER HALLI | INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

Q. How did your passion for art begin taking shape for you—at home, school, a mentor, and other artists who inspired you or a personal experience that started the fermenting process?

A. I was raised in the Roman Catholic Church where we breathed sacraments and rituals. Viewing my childhood from a distance, Eleanor Heartney recounts it aptly: “Catholicism is capable of igniting youthful imaginations and inducing a highly visual and sensual approach to the world. This is the side of Catholicism, which radiates from the flicker of candles illuminating the darkness of Easter morning, which flutters in the voluminous drapery of the ever-serene Virgin Mary, which finds a terrible beauty in relics of bones and blood and ancient dust”. Thus, my current work reverberates tones of a topic I unsuccessfully endeavored to shy away from – religion.

Q. How would you describe your artwork, in terms of materials or mediums? Has it changed or evolved since formal training and what are your goals for it?

A. The objects I create are made of clay, paper, ink, sugar, metal, and fiber. I find fascination in the transformation of materials as they become metaphors for disruption caused by loss, travel, time and memory. Materials as they relate to history and my place within it are determined as I engage with imagery that represents my experience. With hints of blue, a color of impossibility as we try to reach the horizon or the perfection of the Virgin Mary, my new iconography is compiled in the form of a grid, representing structure, boundaries, continuity and repetition.

I began graduate school with a knowledge and focus on the functional craft world – largely concerned with form. Over the three years I have adopted a practice where form, concept and context must support each other equally. By owning my Catholic roots, I am bridging laden history with a new, contemporary and layered approach to religion in art; a topic considered unsettling and unaccepted in recent history.

Q. How important is a personal style to you as an artist or does your work reflect larger social and cultural issues?

A. Religion is a dividing reality in society with Catholicism’s (long overdue) exposure covering the pages of media. I look not to confront the patriarchy, but to acknowledge the quieter teachings of the church, how it forms us as people and seek to bridge a gap. As a US citizen and New Zealand resident, the Christchurch attacks had a profound effect. It happened as I was installing four large-scale works, listening to the memorials, kiwis greeting each other with ‘assalamu alaykum” and one week on, watching New Zealand’s embrace of a public Islamic call to prayer. A pivotal moment. It speaks tomes regarding mysteries in religion, often practiced behind closed doors.

Q. Has being a woman affected your work and others’ perception of it? How do you feel about being a part of a woman’s art organization?

A. I began working in ceramics as a potter, solely firing kilns fueled with wood. This is a practice quite dominated by men. Many of my mentors are men. They write letters of recommendation and advice in my work and opportunities. While grateful for their guidance, I seek out women with an effort to challenge perceptions and provide mentorship to the next generation. Being part of organizations such as the NAWA, we have the opportunity to empower women by providing accessible platforms of inclusion and support.